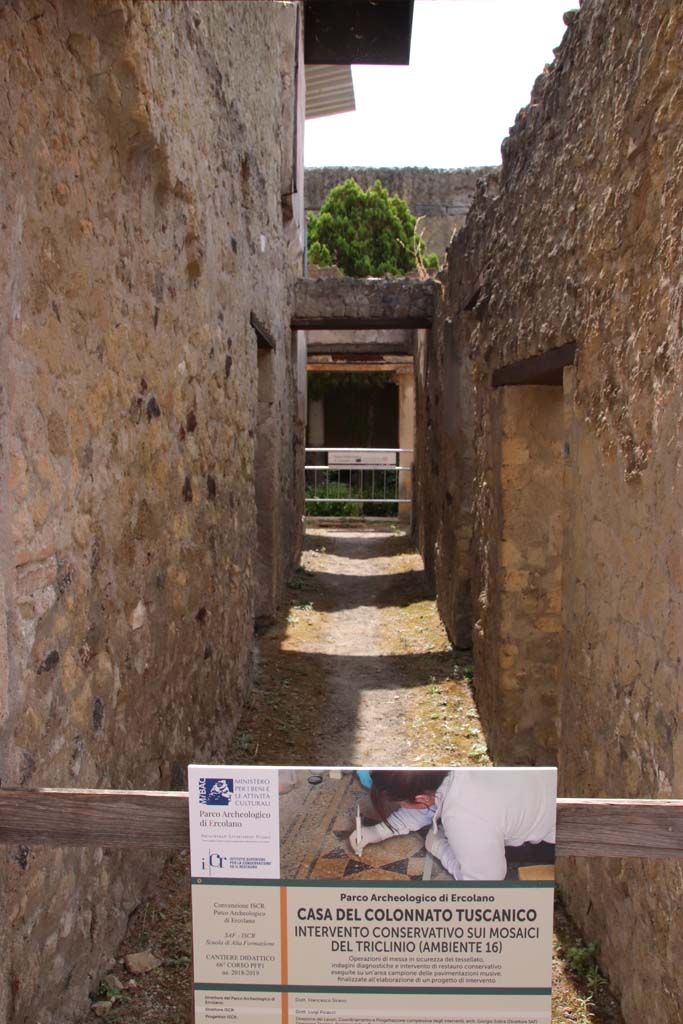

Herculaneum VI.26. Rear entrance

of Casa del Colonnato Tuscanico, linked to VI 17.

Excavated 1959-61.

Wallace-Hadrill wrote that this was the doorway to the Service quarters at back of peristyle, 3 rooms, no decorations, with back door at no.26.

Stairs from street to upper apartment at no.27. Clear example of multiple occupancy in last phase.

See Wallace-Hadrill, A., 1994. Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. New Jersey: Princeton U.P. (p.206)

VI.26 Herculaneum, September 2016. Looking towards doorway on east side of Cardo III Superiore.

On the left of the doorway is the window into the kitchen. Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

VI.26 Herculaneum, October 2014.

Looking towards doorway on east side of Cardo III Superiore. Photo courtesy of Michael Binns.

VI.26 Herculaneum, October 2023.

Looking

east along corridor leading to peristyle, under renovation. Photo

courtesy of Klaus Heese.

VI.26 Herculaneum, September 2019.

Looking

east along corridor leading to peristyle. Photo courtesy of Klaus

Heese.

VI.26 Herculaneum, photo taken between October 2014 and November 2019.

Looking

east along corridor leading to peristyle. Photo

courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

VI 26, Herculaneum, September 2015.

Looking east on Cardo III Superiore to rear doorway to peristyle area.

Above the doorway are the holes for the support beams for an upper floor.

The main entrance would have been on Decumanus Maximus, at VI 17.

VI 26, Herculaneum, September 2015.

Looking east along the long corridor towards peristyle, from rear entrance doorway.

The doorway in the north wall, on the left, leads into the kitchen.

The two doorways on the right lead into two rooms used as storerooms/cupboards in the services area.

VI.26 Herculaneum, August 2013.

Looking east along corridor towards peristyle, from rear entrance doorway. Photo courtesy of Buzz Ferebee.

VI 25/26, Herculaneum, September 2015. Looking south-east across dividing wall into kitchen of VI.26.

VI 26 Herculaneum, September 2015. Looking south from VI.25 into the kitchen of VI.26.

The latrine can be seen in the south-west corner, on the right. The lararium was found on the south wall between the doorway and the latrine.

VI.17/26

Herculaneum. May 2004. Looking towards south wall with remains of lararium

painting. Photo courtesy of Nicolas Monteix.

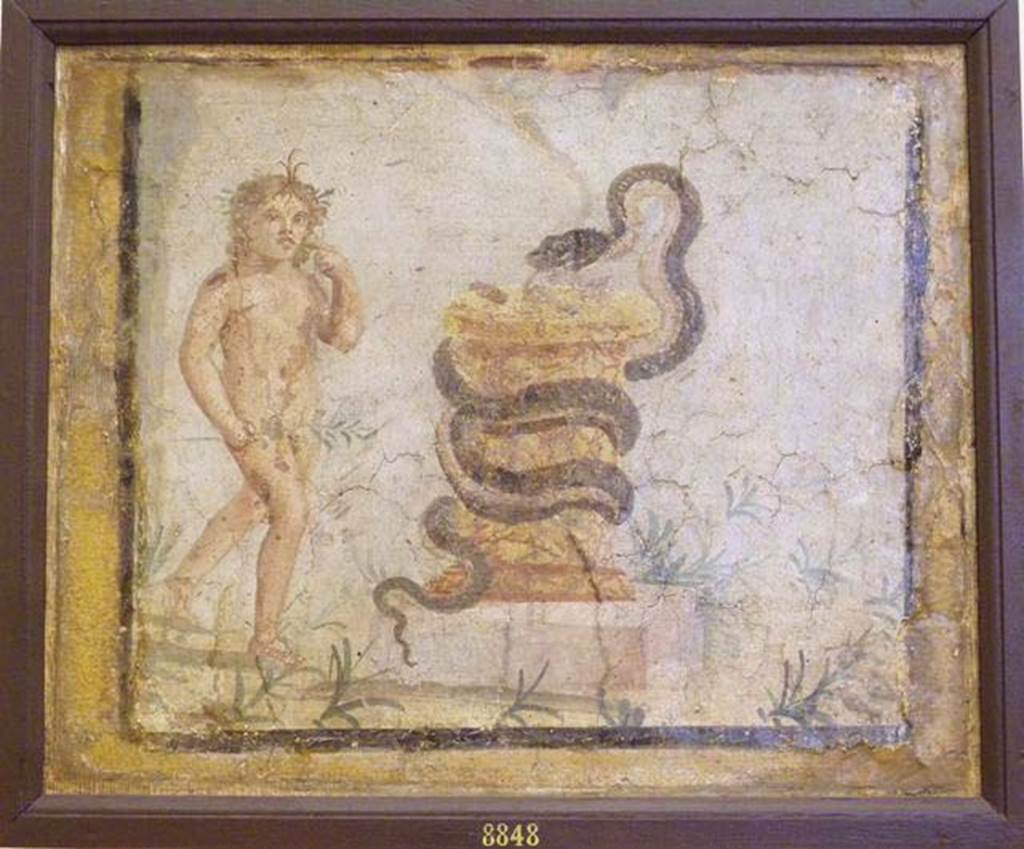

VI 26 Herculaneum, 1972. Remains of lararium painting on south wall of kitchen.

VI 26 Herculaneum. Lararium painting found 21st December 1748 by the Bourbon tunnellers.

Naked Harpocrates on the left of a yellow marble altar, the altar entwined with a serpent approaching the offerings.

Now in Naples Archaeological Museum. Inventory number 8848.

According to Pagano & Prisciandaro, this lararium painting was found in the kitchen?

See Pagano, M.

and Prisciandaro, R., 2006. Studio sulle

provenienze degli oggetti rinvenuti negli scavi borbonici del regno di

Napoli. Naples: Nicola Longobardi.

(p.205).

Other references AdE, I, 36, 207, Diario 267, St.Erc.104.

CIL IV 1176.

A note says “The space of the cut seems to coincide with that of the plaster of the kitchen of the House of the Tuscan Columns” see F. De Salvia in Hommages a J. Leclant, III, 1994, pp.145 onwards.

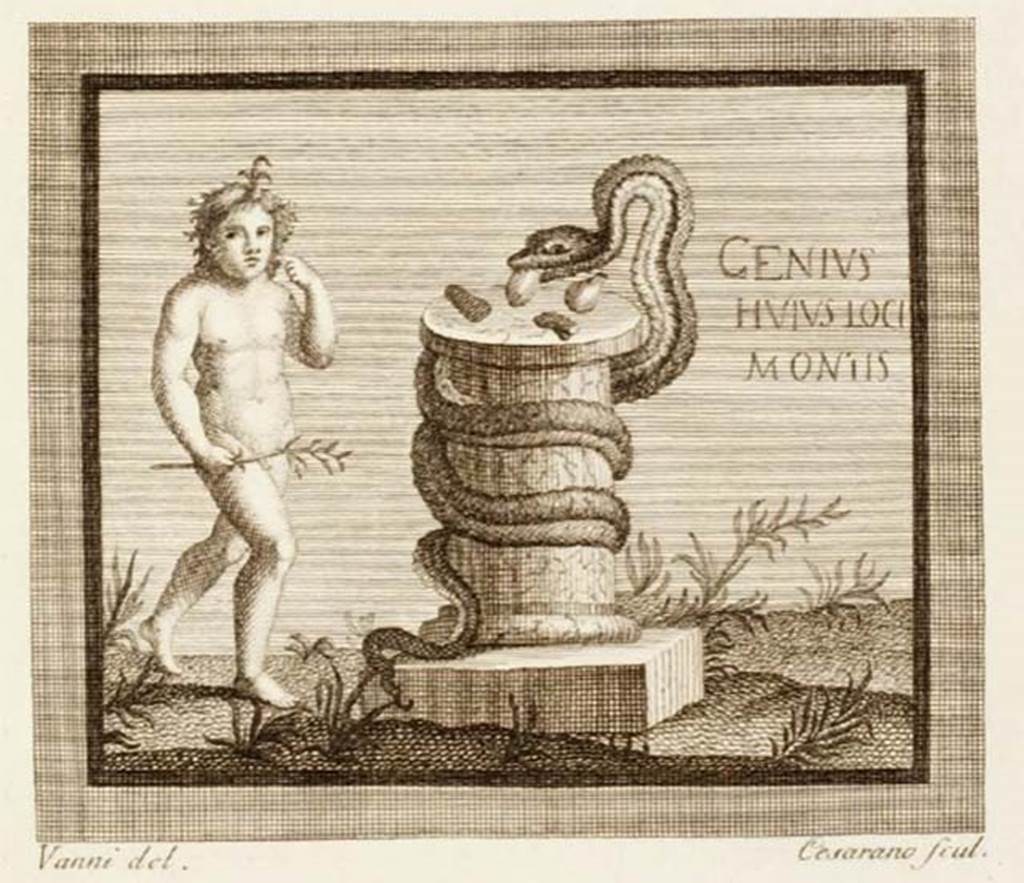

According to Rocco, the incision made in the 1700’s of this painting in the Pitture di Ercolano recorded the inscription, next to the altar, the phrase Genius huius loci montis: it was believed that the serpent was the protector of the places where it lurked.

See Bragantini, I

and Sampaolo, V., Eds, 2009. La Pittura Pompeiana. Verona: Electa. (p.430, no.223).

VI 26 Herculaneum. 17th century incision, including the inscription Genius huius loci montis (CIL IV. 1176).

See Antichità di Ercolano: Tomo Primo: Le

Pitture 1, 1757, Tav. 38, p.207.

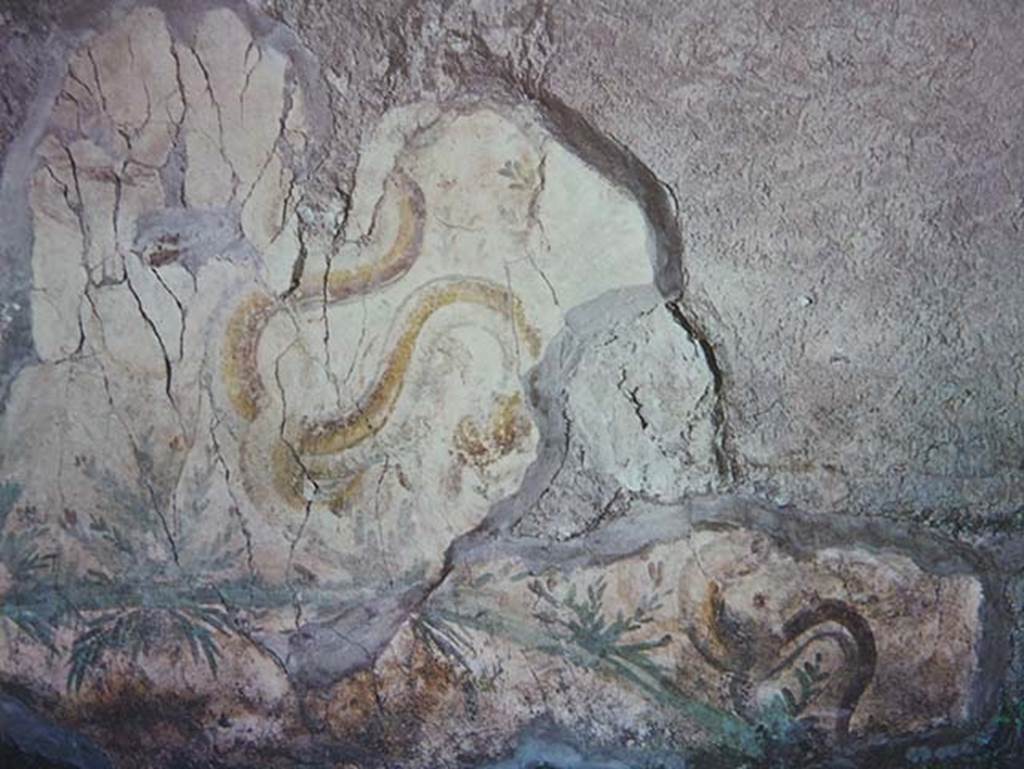

VI 26 Herculaneum, September 2015. Looking east through window into kitchen with bench and remains of lararium with painted serpents.

Leaning against the north wall was a large masonry bench which was used as the kitchen. The latrine was situated in the south-west corner.

The walls of the rooms were entirely in opus incertum: the west and south wall were reasonably preserved; the east wall was partly destroyed by a Bourbon tunnel, and the north wall was missing a large area above the kitchen bench.

The room had flooring of simple beaten earth, and the walls were not decorated with the exception of the lararium painted on the south wall.

VI.17/26

Herculaneum. May 2004.

Looking east across

kitchen towards east wall, and doorway to corridor in south wall. Photo

courtesy of Nicolas Monteix.

VI.17/26

Herculaneum. May 2004. Looking towards east wall. Photo courtesy of Nicolas

Monteix.

VI 26 Herculaneum, September 2019.

Looking east towards peristyle from rear corridor. Photo courtesy of Klaus Heese.

The smooth shafted Tuscan columns, painted black or yellow to a third of their height and white above, gave the house its name.

See Guidobaldi, M.P. and Esposito, D. (2013). Herculaneum: Art of the Buried City. U.S.A, Abbeville Press, (p.191).

According to Jashemski, this peristyle garden was enclosed on four sides by a portico supported by seventeen columns, those opposite the entrance of the large room being double. The garden was made accessible by passageways, one from the atrium, another from the street on the west.

See Jashemski, W. F., 1993. The Gardens of Pompeii, Volume II: Appendices. New York: Caratzas. (p.271)

VI 26 Herculaneum, September 2015. Looking towards peristyle from rear corridor.

Cardo III Superiore, Herculaneum, September 2015. Looking south from between VI. 26, on left, and Ins. VII, on right.

(Inventory number 110127, and see p.659 in Ruggiero, Scavi, etc., (record of 11 September 1874).

See Waldstein, C. & Shoobridge, L. (1908). Herculaneum, past, present and future. London, Macmillan & Co. Ltd., (p.77).

Waldstein and Shoobridge also wrote

“Before leaving the town proper, we must say something of the small portion excavated in the nineteenth century, and still exposed, often called the “Scavi Nuovi.

This part of the city sloped steeply to the south-west and ended in a sharp cliff; and strong and elaborate subterranean rooms were needed to keep the last houses level. Two streets were laid bare, crossing one another at right angles. That running down to the sea has a fine vaulted drain, 0.60m broad and 1.05m high, fed by various small drains and gutters. At the edge of the cliff it empties into a well-shaped opening of unknown depth, but certainly more than three metres.”

See Waldstein, C.

& Shoobridge, L. (1908). Herculaneum,

past, present and future. London, Macmillan & Co. Ltd.,

(p.76-77).

See Ruggiero, M. 1885. Storia degli Scavi di Ercolano ricomposta su’ documenti superstiti. Napoli. (pp. xlvi-li), for the whole description of “Scavi Nuovi”.

Cardo III Superiore, Herculaneum, September 2015. Drain in road.